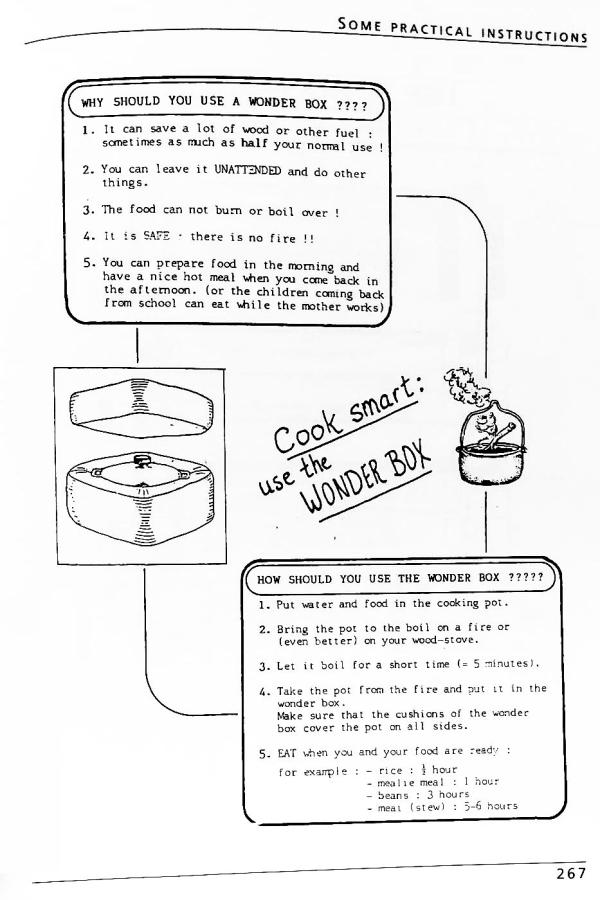

Cooking in a hot box / hot bag saves electricity while reducing our carbon footprint. Food takes only slightly longer to cook than on the stove, and can be left unattended (it doesn’t burn or boil over, and doesn’t need to be stirred).

I even find that stews and soups cooked like this tastes better and more fragrant. Rice is more fluffy and evenly cooked.

A hot bag can also be used to keep things cool – more efficiently than a cooler box.

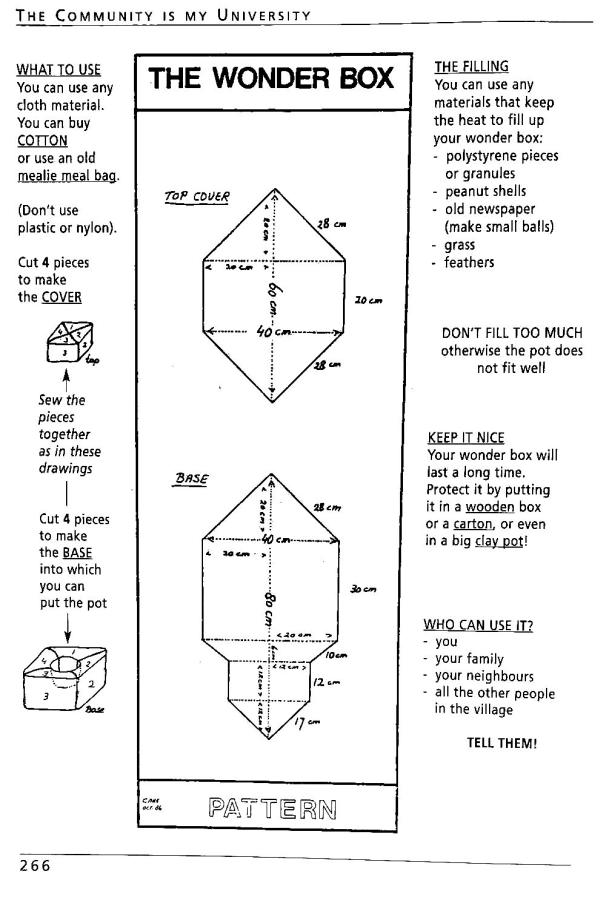

This beautiful book on community development and rural health, has instructions for rural women on how to make a ‘wonder box’ out of old cloth such as old linen mealie meal bags and stuffed with insulating peanut shells, grass, feathers or old newspaper.

You don’t need a box at all though. Some warm blankets work just as well. Hikers know this trick: you only need one little gas cooker for a 3-course meal. Boil a pot of rice, wrap it in your sleeping bag, then prepare your soya mince sauce (which cooks much better, without burning, in another sleeping bag), while you cook the dried vegetables (or make a nice cup of Milo).

At sea level, water boils at 100°C. For every 300m rise in altitude, the boiling point of water is about 1°C lower. So at the top of Amphitheatre, at 3200m, water boils at 89°C. At high altitude food simply takes longer to cook – just something to keep in mind.

For my kitchen I recycled an old kiddies’ duvet that had gotten lumpy. I use this regularly to cook rice, stews, soups – anything that otherwise needs prolonged simmering on the stove. It really helps during loadshedding: as long as I get the pot boiled before the power goes off, no problem.

How much electricity (and carbon dioxide emissions) does a hotbox avoid?

That depends on the kind of stove we are comparing it against, and the kind of food we are cooking. Since one needs to bring the food to the boil either way, the hotbox only saves on the simmering time. Food that only takes 15 min to cook on a stove would save only a little electricity; food that has to cook for hours, saves a lot. So the cooking box is particularly useful for meals that require longer cooking times.

1kWh electricity produces approximately 1kg of carbon dioxide emissions.

For those who like actual numbers, Eskom reports that it produced 198 281GWh of electricity in 2022, with 207.2Mt carbon dioxide emissions (plus 32.90Mt ash and 66.65kt particulate matter). Converted that is 198,281 million kWh and 207,200 million kg. Divide kg by kWh to get emissions per energy used.

A typical 1000W stove plate, if set to maximum heat, would use 1kWh per hour, and produce 1kg of carbon dioxide in emissions. So let’s say you simmer food (on level 3 out of 6) then you can assume a typical 1000W plate will consume approximately 0.5kWh per hour on half heat, which equates to about 0.5kg carbon dioxide. Now do that every day. Perhaps you use more than one stove plate at a time. All that adds up very quickly.

Please have a look at the total kWh on your last monthly electricity bill, and multiply that number by 12 to get the number of kg of carbon dioxide your household adds to the atmosphere every year. Now think: you can do something about that. Just dig out an old blanket and start today!