It’s been two years since we installed solar power. How has it worked for us?

The details may be complicated, but the conclusion is not: PV works.

The biggest hurdle for many remains the cost – despite tax breaks and the lowest-ever prices. Before ‘splashing out’, they want to know: Does solar power really work? Money-wise and otherwise?

In this blog I answer these questions and others that came up in a recent climate change event, where the audience showed surprising interest in some of the finer details. I cover various decision about the design, wiring, settings on the inverter and geyser, and behaviour. Then I discuss our results in terms of power generation and use, money matters, and feeding back to the grid.

To me the biggest tragedy is that solar power dates back to the 1880s and has been mass-produced since the 1960s! What happened? Skullduggery? Knowing today about some of the dirty tactics fossil fuel companies have used to protected their interests, probably yes. Let’s end this injustice.

Next month is World Energy Day (22 October). I hope this blog will help some who are still unsure about PV, make a positive decision.

Design

Various suppliers and websites can help you design a system that matches your lifestyle, your needs and your budget.

We were lucky to have an expert friend, an electrical engineer who was involved in the design and construction of the de Aar solar farm. He gave us an initial design, along with all the numbers. His calculations included many engineering details, such as hourly data on solar irradiance (how much energy shines from the sky), based on the local latitude and altitude, and how much is collected by the panels, based on temperature, windspeed, albedo, and the angle and orientation of our own roof. After accounting for various losses, you get an estimate of the actual DC voltage generated by the panels, and the final AC power you can expect to get out of the system.

We had saved up for solar power, and were willing to spend a bit extra to get the most out of it.

Panels: We installed our panels on the garage roof, as it was most north-facing, with the least shade. The panels are the cheapest part of the system, so we decided to install as many as would fit on the roof (17 panels).

Batteries: We did not consider a solar system without batteries. Apart from reducing our carbon footprint, power storage was the main attraction. Despite the price tag, we decided to get two 5kW batteries. We felt that the extra investment would pay itself off in avoided grid usage, and would help during loadshedding and longer outages.

This has definitely worked in our favour. Two batteries, once fully charged, supply our needs through supper time until well past midnight, often until dawn – depending on how much power we use in the evening. During the day the batteries help supply the geyser and other power-intensive activities, especially on cloudy days.

Inverter: we decided to spend a few thousand Rands extra on a large 8kW inverter, instead of the standard 5kW inverter recommended for households of our size. We reasoned that with 17 panels, peak power generation would be well above 5kW on a sunny day, and we wanted to harvest this power.

Was the 8kW inverter worth it? In retrospect, no. On a sunny summer day, power production reaches 8kW for many hours. This is far more than we can utilize, and most of it gets exported to the grid (i.e. ‘wasted’ from our perspective, as we don’t get paid for this). The 5kW inverter would simply have capped generation at 5kW.

Power production in mid-winter anyway peaks at just above 5kW, and on a sunny winter day we still have too much, exporting around 30% of the power generated. On overcast days the system never reaches the 5kW limit. So… a 5kW inverter would have sufficed. If the municipality paid us for the electricity we export, it would be a different story. Lesson learned.

This blog by the editor of TechCentral, has other useful details on the design side. A ‘solar for dummies‘ article by one of the solar company is also helpful. (We went with another company and were very happy with their service.)

Wiring

If you install PV power, while remaining connected to the grid, the distribution board has to be split into ‘essentials’ (powered by PV during grid outages) and ‘non-essentials’ (not powered by PV during grid outages). The main decision is what is ‘essential’ and not.

We were advised to wire the geyser, stove/oven and pool pump to the ‘non-essential’ section. That is because together they can draw more than 8kW – the limit of what our PV system can supply. Over-loading the inverter would cause the system to trip.

We also decided to put the granny flat on the ‘non-essential’ circuit, because we cannot control what tenants do during loadshedding, and this might cause unnecessary conflict.

What does this mean in practice?

When the grid is available, everything is connected and can be powered by the PV system, even the ‘non-essential’ circuits. If ever the total load exceeds the 8kW limit of our PV system, the grid supplies the excess.

However during grid outages, the ‘non-essentials’ are not powered: the pool pump doesn’t run, the geyser doesn’t heat and the stove doesn’t work (even when there is plenty solar power).

Ok, so the geyser simply catches up when the grid comes back online, drawing on the PV system as before, and we don’t notice loadshedding in that regard. However I found it annoying to have no stove during loadshedding, when I could be running it on solar power.

So we got an electrician to install a special switch, allowing us to connect the stove/oven to the ‘essential’ part of the DB temporarily. We just have to be aware, and not use too many appliances at the same time, and then switch the stove back to the ‘non-essentials’ afterwards. This was a brilliant idea.

Settings on inverter

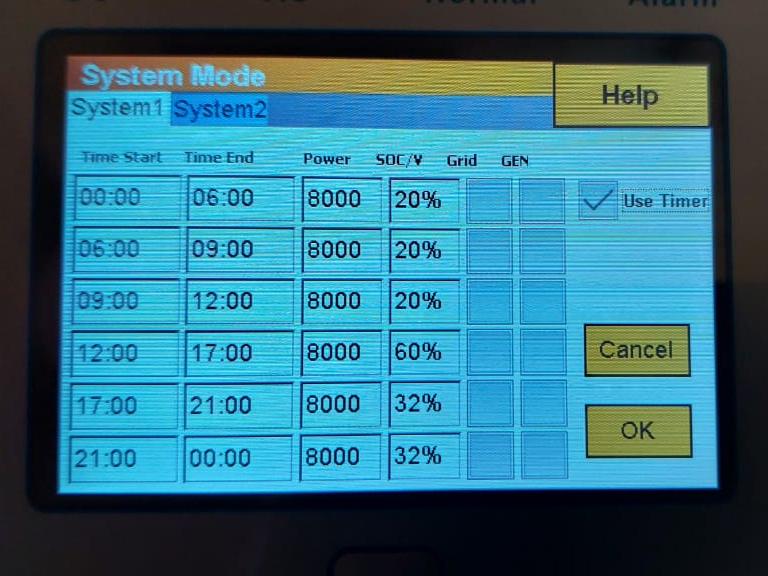

Another decision point is how to program the inverter. Like, whether to export or not, whether to charge the batteries from the grid, and especially, how and when to use the batteries.

You don’t want to run the batteries flat, as this reduces their lifespan. In fact, it is advised not to run batteries much below 20% charge. So one should program the inverter to switch off the batteries when they reach 20%.

We also made the decision never to charge our batteries from the grid, only from solar power. Converting grid power to battery and back just wastes energy. We can always get by until sunrise.

Geyser controller

The geyser draws a huge amount of power, and we avoid using the grid for this, if possible. A digital geyser controller turns on the geyser during peak daylight hours. Keeping it heated all the time would be a complete waste.

Our geyser is set to come on at 10h30 heating to 55°C; and again at 12h00 heating to 65°C. This is enough for up to four hot showers in the evening. Spreading the heating over two periods gives the batteries a chance to charge as well, especially on partly cloudy days.

In the early morning hours the geyser comes on briefly to top up the temperature to 45°C, for one hot morning shower. Usually the water is still warm from the previous day and it heat for 10 minutes or less.

On weekends the settings are slightly different. We keep tweaking the timings to minimize our grid usage.

We also finally installed a geyser blanket, which cost all of R300, to reduce heat loss in winter.

Behaviour

Installing solar power was only the first step. Then we had to learn how to use it.

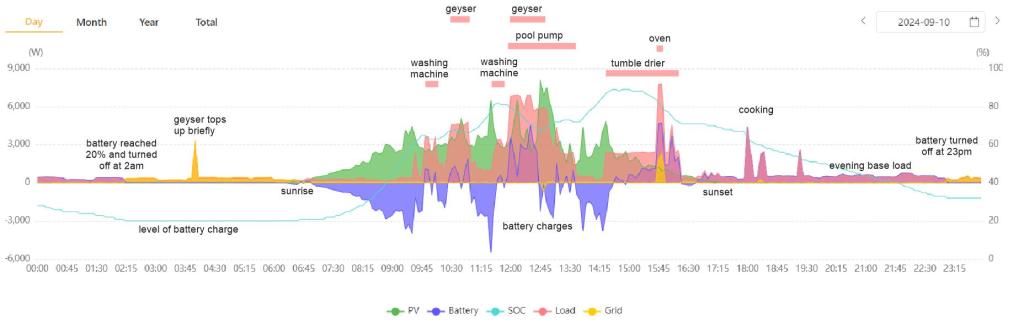

In the beginning we got on average 60% of our electricity from the solar system. Now we are getting over 80%, from the same system.

We have learned a LOT. From the graphs generated by the PV app we have become very aware how much electricity different activities and appliances require, how much power is generated in different seasons and weather conditions, and we have learned how best to utilize it.

We have shifted energy-intensive activities to daylight hours: washing machine, dishwasher, or when necessary, the tumble drier. We also use many of the electricity saving methods described on the climate change booklet checklist. It just becomes a way of life.

The pool pump draws a lot of electricity (yes we have a pool, eish!) We use a simple manual timer, set to the brightest times of the day: in summer it runs from 8am to 4pm, in winter from 10am to 2pm, which is enough to keep the pool clean. On overcast, bad solar days we turn the pool pump off.

Power generation and use

Through the seasons, days get shorter or longer, more sunny or more cloudy. Our best solar month so far was January 2023 (1124kWh generated), the worst was May 2023 (480kWh) – which had lots of cloudy weather and short days.

Comparing monthly graphs from 2022 with 2024, the amount of solar power generated (‘PV’ – green bars) remained around 800kWh per month, regardless of time of year. Our home electricity usage (‘Load’ – pink bars) was also fairly constant, between 600 and 700kWh per month.

However the amount of electricity exported to the grid (light orange bars), was a lot more in the beginning (400kWh), down to 240kWh per month now (meaning we now throw away less of the power that we generate).

The amount imported from the grid every month (dark orange bars), which we had to pay for at the usual rate, decreased from 280kWh to 120kWh per month, more than halving our remaining electricity bill.

In other words, in 2022 our solar system supplied 58% of our electricity usage, in 2024 it supplies over 80% on average.

How? Partly by making the various adjustments described above. But mainly by using our batteries throughout the day. In the beginning we only drew on the batteries at night (or during loadshedding), not otherwise. Now we use them whenever demand (load) exceeds PV generation.

Economics

Does solar power make financial sense? Yes.

In 2022, our electricity bill would have been on average R1600 per month, based on our usage. That first year we paid only R670 (imported from grid), thus saving R930 a month (58% savings).

In 2024 electricity would have cost us R1880, but we paid R350, saving R1530 a month (81% savings).

In total so far we have saved about R30 000. We could have saved more based on what we know now.

Our system cost around R210 000 to install in 2022. If we assume inflation remains at 6.4% (the average over the past 2 years), and that electricity prices increase at the same rate, the savings would pay off that amount in 10 years. However for the past 8 years electricity prices have increased by 12% every year, double the inflation rate! If this trend continues, total savings would reach R210 000 in just over 5 years (not considering the interest earned).

As mentioned, we had saved up for it, and paid in cash. Had we put the expense on our bond, the savings would pay off the expense plus interest, after about 12 years, without putting in a cent extra.

Embedded rooftop solar PV

When you install rooftop solar, you have to register – here are the guidelines.

In our experience, until our system was registered, the municipality continued to bill us at our pre-PV consumption levels, despite repeated confirmed meter readings.

Once our registration went through, the municipality came and installed a bi-directional meter. Our excess payments were then credited back to us (not paid out in cash), against our monthly bills.

Do you get paid for power you export to the grid?

Yes and no. eThekwini municipality allows embedded power, at least in principle. But in our case it makes no financial sense. Here’s why:

Currently, we pay R 2.97 per kWh, with service charges built in, same as everyone else. If we wanted to earn money on our exports, we would have to sign up for the Feed-in Energy scheme. However, the price structure is not in our favour.

According to the 2023/24 tariff booklet, we would earn R1.44 per kWh (similar to what the city pays Eskom), but we would have to pay an ‘Ancilliary Network Charge’ of R126.86 per kVA (based on the inverter size). On our 8kW inverter that would amount to R1015 a month. 1015/1.44=705.

In other words, we would only start earning on exports above 705 kWh, which is more than we export currently. So for us the feed-in system makes no sense financially – we would spend more than we would earn.

So we simply donate surplus electricity to the city (rather than dumping it) – say ‘thanks’, eThekwini! Subsidizing the city is ok for now, but if too many people pour their excess power into the grid, eventually it runs in reverse, and you get negative electricity prices, which is becoming a conundrum in other parts of the world. (I’m sure there is a solution for having ‘too much’ free energy! The market will respond, don’t worry.)

Back to our local situation: with a 5kW inverter, one would start earning on exports above 440kWh, but then we would probably export less, as the smaller inverter would simply cap production at 5kW.

Variable daily rates – with highest prices during peak demand, and lowest prices during low-demand and high-supply periods, can be a powerful incentive for users to shift their consumption. A system like this is in place already (‘Time of use’ fee structure), but the minimum charge of R234.24 again means this only makes sense for high end users and businesses. A variable fee structure would not be fair for low-end users who tend to have less freedom of choice and less flexibility.

Let me end there. I hope someone finds it useful.