Disasters strike at random, and catch people off-guard. People also panic when they don’t know for sure what to expect. Disaster readiness and early warning saves lives. Good information can give one peace of mind, as well as the confidence to act.

With climate change, flooding events get more intense and happen more often. On Monday this week, Dubai suffered a ‘rain bomb‘ that dumped a year’s worth of rainfall in a few hours.

Yesterday, after a work-related webinar on climate modelling, a colleague asked if forecasts can “predict the absolute intensity of rain in advance. For instance when we had the floods in January, they knew it was going to rain but had no idea of the volume, and the fact that it was going to happen overnight, instead of spread out over 2-3 days, which would not have caused such damage!”

This question prompted me to write this personal account of the Durban floods in 2022.

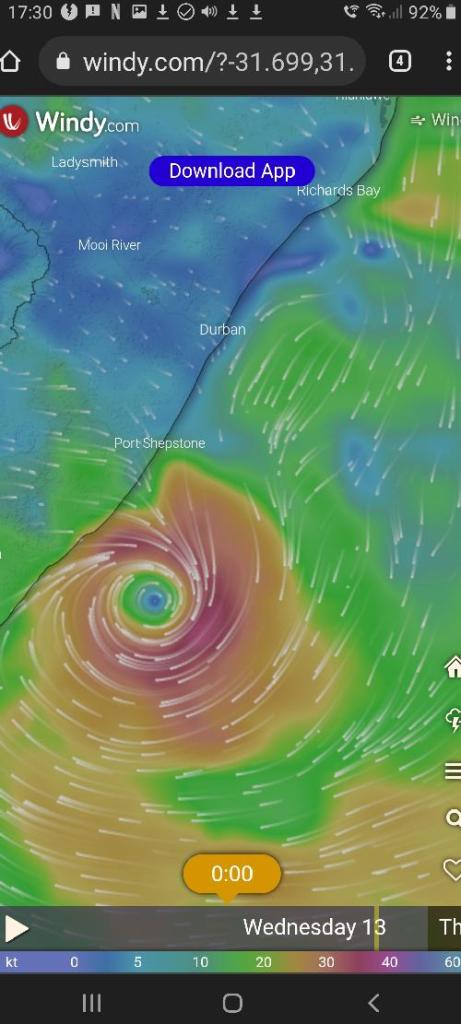

For most of my life I have been fascinated with geography and weather. One day, by chance, I discovered Windy.com. The first thing I saw was a swirling spiral off our coastline, between Madagascar and Mozambique, which puzzled and intrigued me. I shrugged, and almost forgot about it – except that it turned out to be Cyclone Idai, the deadliest cyclone ever to hit our continent.

I was hooked. Sometimes I simply ‘surf’ the globe, looking at the wind, including the jet stream at different altitudes, or rain, or thunder storms, or ocean currents. I have also started using these online forecasts to inform the neighbourhood via our chat group, and so became known as the ‘weather woman’.

In April 2022, Durban was struck by the worst flooding disaster in recorded history.

Our family are fortunate enough to live in a brick building, and suffered minimal damage. But the hundreds of thousands who live in precarious houses and shacks can lose their entire livelihoods in a single day.

Afterwards the big question was: did the weather forecasts not see this coming?

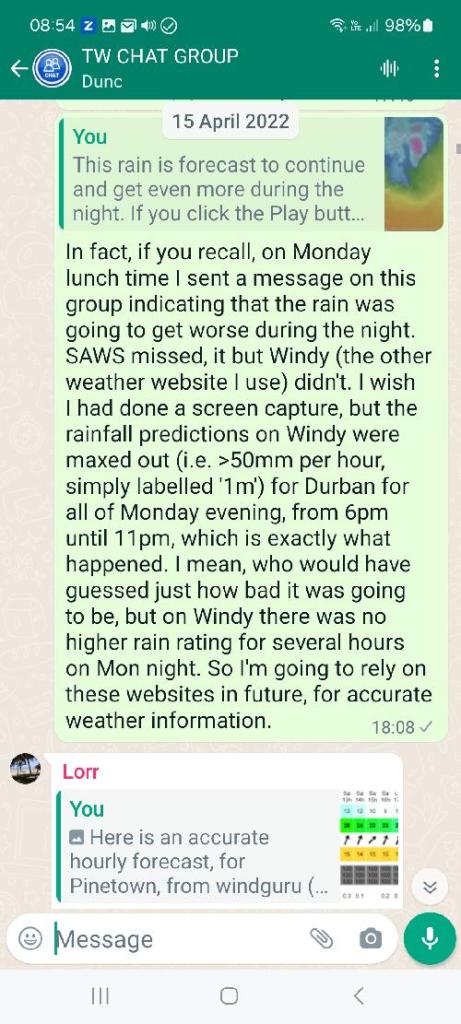

In fact, Windy.com did see it coming, very clearly. The rain forecast on 11 April was completely maxed out, showing the highest possible category. By late morning it was predicting 50-100mm per hour, from 6 to 11pm that evening. It turned out to be uncannily accurate, the rain fell exactly as predicted.

I had not used Windy in this context before, so my warning was worded simply and carefully, referring folks to the original source. I did not consider then that everyone would not be familiar with such an app, be able to interpret it, or even have sufficient Internet access.

The South African weather service (SAWS) had failed to issue serious warnings, which was embarrassing to say the least. An event of this magnitude should have rung all the alarm bells.

On 12 April, a belated Media Release from SAWS pointed out that “at 16h00 yesterday, a Level 5 warning was issued” and that this “was subsequently escalated to a Level 8 warning at 20h00”. They also claimed that “the exceptionally heavy rainfall overnight and this morning exceeded even the expectations of the southern African meteorological community at large.” There were explanations of what “orange level 9”, “yellow level 4” and “orange level 6” warnings mean, but I find this mix of colours and numbers quite confusing.

“Could this rain system be attributed to global warming and climate change?” the article asked, then gave a difficult-to-understand and misleading answer: “No, as weather scientists we cannot attribute individual weather events occurring on short timescales …” and so on. The last sentence of the paragraph finally admitted, “…heavy rain events such as the current incident can rightfully be expected to recur in the future and with increasing frequency.”

That last sentence should have come first. Why? Because people need to know this, we need to address climate change, urgently. (And it should have been translated into plain English: There is very a good chance that this disaster would not have happened, or would have been only half as bad, if it wasn’t for climate change. And that is the truth.)

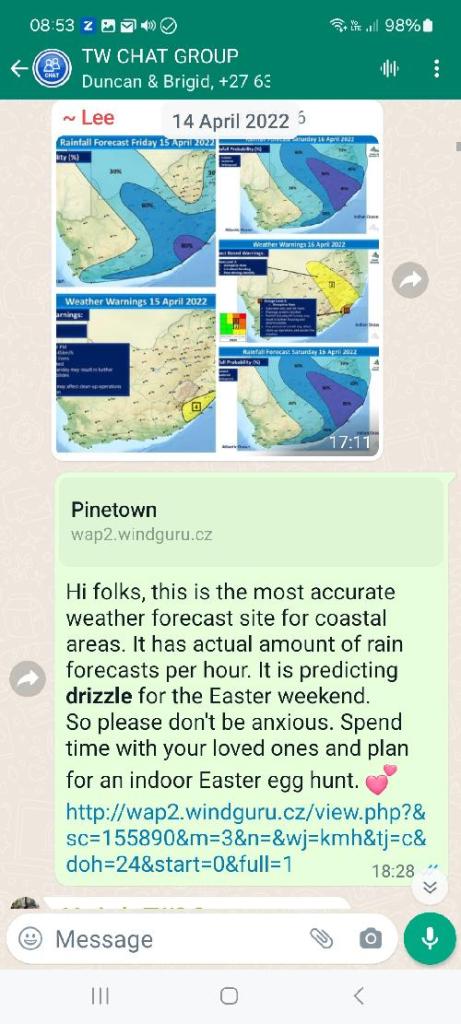

When it started raining again two days later, SAWS was on high alert and issued a level 5 orange warning for our area with “possible localized flooding”. A weather forecast circulated on social media, which described the 11 April flooding disaster, as “quite significant amounts of rainfall.” Huh? Pardon? So… what exactly does ‘level 5 orange’ mean then? Gear up for another disaster?

Meanwhile, both Windguru and Windy were predicting only light rain, so I reassured the neighbours, and recommend a peaceful weekend with indoor Easter egg hunts. It was a non-event.

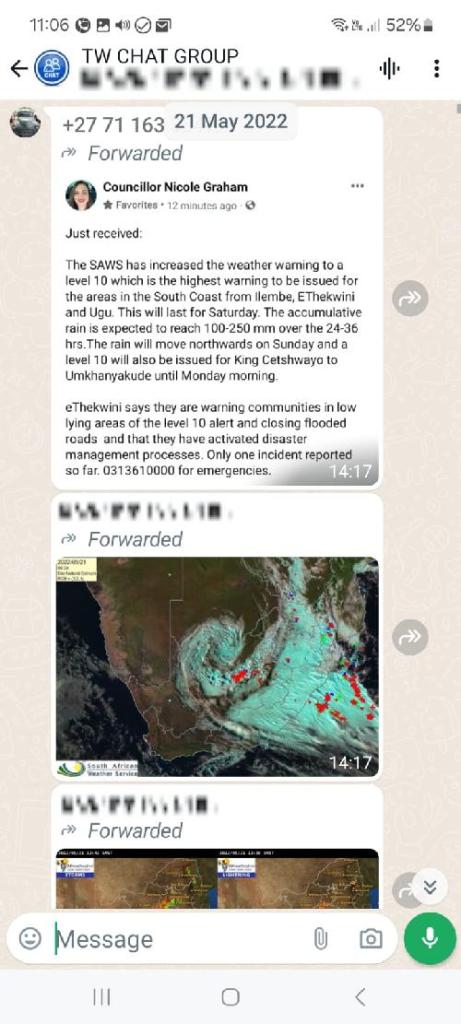

Of course, a few weeks later, on 22 May, we did have another flooding event! This time SAWS released a dire level 10 red warning. (What does ‘level 10 red’ mean? – compared to the April floods?) Now people were worrying: was this going to be even worse? Some folks had gotten badly flooded, and were panicking. The social media went crazy and people didn’t know who to listen to. Many folks in our neighbourhood have smartphones, but can’t or don’t access the Internet. Even if they did/could, where exactly would they look? They rely on forwarded information.

So, a big question for me is: if Windy.com was able to predict the exact timing and amount of rain, why did the SAWS forecast system get it so wrong? I also don’t find those generalized warnings with colours and levels very helpful. Personally. I want to know how much it will rain, when, for how long. When it rains, I want to know if it will get worse or let up, an hour later. Then I can judge. I can look outside and decide. But maybe other people want to know other things.

And then, how does this information filter down to the people? I don’t know how it works. I’m sure information on a computer has to pass through the climatologists whose job it is to keep an eye on the predictions, through levels of management, through broadcasting stations, through journalists and editors, to finally end up on people’s TVs and phones for instance, in a useful format and with meaningful content.

How do the numbers and maps get translated? What pictures, colours, numbers and words are used? How do you make it meaningful in real life? What happens when messages get translated into other languages? How are message communicated? Who says what, when, how often, where and how? How is information interpreted and transmitted? Through which media? Who sees, reads and hears it? How, where and when is it passed along? By whom, to whom? At what time? How accurately are messages passed along? How are they understood? Is the information trustworthy? And is it trusted? Do people know how to respond? And then, do they act on it?

Science considers type I (alpha) and type II (beta) errors. Type I errors are ‘false positives’: raising a false alarm when there’s nothing to worry about, ‘crying wolf’, believing a falsehood. Type II errors are false negatives: missing a real warning, failing to raise alarm when there really is something to worry about, missing a truth.

One can see both types of errors in the Durban floods: first a lack of warning of impending disaster, so people say “Why didn’t you tell us?” followed by over-reaction, so people say “That wasn’t so bad, what was all the fuss about?” Both types of errors erode trust.

What about liability? After a deadly flooding disaster in July 2021, in the Ahr Valley, Germany, local authorities had come under investigation “for negligent homicide and negligent bodily harm as the result of possibly failed or delayed warnings or evacuations of the population”, for acting too late in sending flood warnings. Two days ago, the investigation was finally dropped because “it was an extraordinary natural disaster” that “far exceeded anything people had experienced before and was subjectively unimaginable”. Is this sufficient reason to escape liability in a warming world where disasters are coming ever faster and harder?

Looking back over the past 20 years or so, with our weather fetish, my hubby and I had been consulting a website called Windguru, a simple, utilitarian service (started by a Czech windsurfers of all people!) This used to produce incredibly accurate forecasts (originally only in coastal areas), predicting exactly how much it would rain, and when, down to the hour. Based on this we would plan camping holidays, time hikes, and decide when to wash clothes.

I say ‘used to’, because these past few years I have the impression that it has started to underestimate rainfall – in our province at least. In years gone by, <1mm was reliably ‘light drizzle’ or negligible spots of rain. Now we regularly see proper, driving rain, when <1mm is forecast. This is totally anecdotal, but I wonder if the weather models are perhaps not able to keep up with climate change?

At the same webinar that I mentioned earlier, someone asked, “What can we do to help the most vulnerable, people living in shacks, in valleys below the 100 year flood-level, people who won’t want to flee because their entire livelihood is at stake?” Research is being done in this critical area, for example on the Quarry Road Informal Settlement in a flood plain. We need solutions, and quickly. The next flood is just around the corner.

That’s where I leave it. My scientific brain cells are whirring and wondering. I have no real answer, only lots of questions. Sorry.